Links

Sheba Medical Centre

Melanie Phillips

Shariah Finance Watch

Australian Islamist Monitor - MultiFaith

West Australian Friends of Israel

Why Israel is at war

Lozowick Blog

NeoZionoid The NeoZionoiZeoN blog

Blank pages of the age

Silent Runnings

Jewish Issues watchdog

Discover more about Israel advocacy

Zionists the creation of Israel

Dissecting the Left

Paula says

Perspectives on Israel - Zionists

Zionism & Israel Information Center

Zionism educational seminars

Christian dhimmitude

Forum on Mideast

Israel Blog - documents terror war against Israelis

Zionism on the web

RECOMMENDED: newsback News discussion community

RSS Feed software from CarP

International law, Arab-Israeli conflict

Think-Israel

The Big Lies

Shmloozing with terrorists

IDF ON YOUTUBE

Israel's contributions to the world

MEMRI

Mark Durie Blog

The latest good news from Israel...new inventions, cures, advances.

support defenders of Israel

The Gaza War 2014

The 2014 Gaza Conflict Factual and Legal Aspects

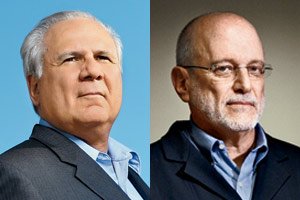

What happened between David Protess and Medill?

UPDATE (7/Sep/2011): This morning, Judge Diane Cannon of the Cook County Circuit Court ruled that the Northwestern University students in the reporting class of former professor David Protess were acting as investigators for the defense rather than as journalists, and were therefore not protected by the Illinois Reporter’s Privilege Act.

Cannon ordered that more than 500 e-mails between Protess and students who reexamined the three-decades old murder conviction of Anthony McKinney be turned over to prosecutors. The university said it is weighing its options, including a possible appeal.

The two-year legal wrangling that led to the ruling lies at the heart of the story below, which takes an in-depth look at the controversial circumstances surrounding the acrimonious departure of Protess from Northwestern and the resulting wounds that have yet to heal among many. "Loss of Innocence" appears in the October issue of Chicago, on newsstands September 15.

* * *

The image is indelible. Anthony Porter, a death row inmate who had come within 48 hours of being executed, had just walked out of Cook County jail a free man. A car was waiting to whisk him away, but before Porter could climb inside, he caught sight of a rumpled-looking, silver-haired man beaming next to a group of exultant college students. Porter ran over, threw his arms around him, and lifted the professor up, up into the raw cold of a February 1999 afternoon, until the man’s feet swung above the cracked concrete lot.

One by one, Porter repeated the act, hoisting each of the five students in turn. Shutters clicked. Cameras whirred. The moment flashed on screens across the United States and around the world, a giddy symbol of justice triumphant and yet another bragging right for the institution that the man had called his professional home for nearly two decades: Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism.

It wasn’t the first time David Protess and his investigative reporting class had grabbed headlines. Three years earlier, he and his students had captured national attention by helping exonerate the Ford Heights Four—four men wrongfully convicted of murder, two of whom were on death row.

The Porter case, however, launched him and his program into the academic and journalistic stratosphere. George Ryan, then the governor of Illinois, cited Protess’s work as the driving force behind his imposition of a first-of-its-kind death penalty moratorium. “Innocence projects,” patterned on Protess’s own at Medill, sprang up across the country, filled with students and lawyers whose idealistic fervor was inspired by the Medill professor and what his class had accomplished.

In the years that followed, more exonerations would come—12 by the time Protess was done, five of which were men awaiting execution. The already estimable reputation of Northwestern’s journalism school grew with each victory. It would all end ugly, of course, in a scandal that dealt a blow to Protess’s legacy and tarnished the university. But there seemed only possibilities on that February day when Protess and his students were lifted up, up in the cold gray, against the backdrop of a jail from which another man wrongfully sentenced to die had, thanks to them, walked free.

It was nearly impossible not to recall that image—arguably the apotheosis of Protess’s nearly 30-year career at Northwestern—when I met him at the spartan three-room suite of Loop offices that houses his new venture, the Chicago Innocence Project. The program, Protess told me when I visited in July, will be a version of what he did at Medill, the first nonprofit journalism innocence project, in fact, in the country. His work force, he says, will consist of community residents, journalists, private investigators, and, yes, students—some, he hopes, from his old stomping ground at Medill. Funding will come from grants, foundation gifts, and individual donors.

On the day I visited, Protess had only begun to move in, and the place had a barren, cheerless feel to it. A couple of volunteers, including one of Protess’s former Northwestern students, were working to spruce things up, tapping nails for hanging pictures, excavating “29 years of memories,” as Protess calls them, from cardboard boxes.

“This will be our storage area,” Protess said, gesturing at a wall. “This will be a lounge for the students. And this,” he said, “is my office.” The room was empty except for a large library desk inherited from the previous occupant and a rug donated by Protess’s son Ben, a reporter at The New York Times. On the wall hung a City Council resolution honoring Protess and his students for their work with the Ford Heights Four and a poster advertising the 1998 National Conference on Wrongful Convictions and the Death Penalty (“where it all started,” Protess says). The desk held a coffee mug, a pencil cup, a single yellow legal pad with curled-up pages, and a couple of framed family photos.

Protess insisted that his digs at Northwestern’s creaky old Fisk Hall were hardly less drab—that they were, in fact, more cramped. Still, the tableau seemed a long way from the ivied grandeur and tradition-bound corridors of the university, where for so long Protess presided as arguably the most famous professor at one of the country’s most prestigious journalism schools. “I’m in the Loop, which is a more appropriate home base for our work than the ivory tower,” Protess said. “It beats spending another year lecturing about the good old days from yellowing notes.”

The good old days came crashing to a deeply bitter end this past April, when Northwestern spokesman Alan Cubbage issued a press release that accused Protess of “numerous examples of knowingly making false and misleading statements to the dean, to University attorneys, and to others” in the case of a prisoner named Anthony McKinney.

Specifically, the release accused Protess of altering an e-mail to “hide the fact that . . . student memos had been shared with Mr. McKinney’s lawyers,” thus causing the university to unwittingly misrepresent itself in court. It also accused him of repeatedly lying about the number of documents he had shared with defense attorneys during a high-profile subpoena fight between the school and the Cook County state’s attorney, Anita Alvarez.

“Medill makes clear its values on its website, with the first value to ‘be respectful of the school, yourself and others—which includes personal and professional integrity,’” the release said. “Protess has not maintained that value, a value that is essential in teaching our students.”

On the day Cubbage issued the press release, Medill’s dean, John Lavine, held a closed-door faculty meeting to which Protess was not invited. In it, Lavine led the stunned professors through a detailed PowerPoint presentation detailing the statements contained in the release.

The allegations were shocking enough. But to many faculty members at the meeting—and, later, to students and outside observers—just as stunning was the scathing tone of the release and the public way the school’s dean had just lambasted a lauded tenured professor.

“People were horrified at that press release. They’re still horrified, and I’m still horrified,” says Donna Leff, a professor at Northwestern and one of the few faculty members willing to talk on the record about the controversy. “The way they treated David made me sick to my stomach, and I would say that even if I hated David. It was untoward.”

Both the press release and the meeting included the announcement that Protess would not be teaching in the spring. Eventually, Protess reached a negotiated settlement with the university and retired. His exit became official in September. He continues to deny the allegations that led to his downfall.

The university says it has moved on, and, indeed, Protess’s investigative reporting class and the Medill Innocence Project he founded have been turned over to Alec Klein, a former Washington Post investigative business reporter.

As a new school term gets under way at Northwestern, however, the first in nearly three decades without Protess, an essential question remains for many: “What I still don’t get is why they would allow the Babe Ruth of their school to be destroyed,” says Charles Lewis, a journalism professor at American University and founder of the Center for Public Integrity, a nonprofit investigative news organization. “Or if not destroyed then impugned to such an extent that he was taken out inside their own school by the suits. It just doesn’t smell good.”

“It’s pretty perplexing,” adds Doug Foster, a Medill professor who attended the closed-door meeting. “To see the most celebrated faculty member on a prestigious journalism faculty in a great university come to this kind of bitter, rancorous, nasty parting with his institution—for a lot of us on the inside, it remains something of a mystery.”

# reads: 198