Secularism is a matter of the free, democratic choice to reject religion, and it is as legitimate as religious belief.

Against the background of the recent Im Tirzu campaign against some of Israel’s world-renowned writers, playwrights and actors, who were presented by the group as traitors just because they are left-wing and openly support Israeli human rights organizations, the current debate about what Israeli youths should be taught about democracy at school becomes especially pertinent.

Toward the end of October 2015, all hell broke loose when the Education Ministry first published an indicator (mehvan) for basic concepts in the teaching of civic studies (ezrahut). The indicator places much greater emphasis than previous versions on the Jewish aspects of the state at the expense of the democratic ones, though it admittedly also goes into much greater detail on the issue of Israel’s Arab minority, though not necessarily in a positive manner.

Immediately there were those who concluded that the indicator was a warning light as to what was to be expected from a new version of the civic studies textbook To be Citizens in Israel – a Jewish and Democratic State, which is supposed to prepare Israeli youths for their matriculation exam in civic studies.

The textbook has been under revision for five years – since Gideon Sa’ar (Likud) was education minister during the 18th Knesset. It was originally published in 2000, during Ehud Barak’s government, when Yossi Sarid (Meretz) was education minister. Presumably the writing of the textbook began during Yitzhak Rabin’s second government, when Shulamit Aloni and Amnon Rubinstein (Meretz) served consecutively as education minister (Aloni was forced to resign under pressure from Shas), though it should be noted that the writing was not interrupted or interfered with during Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s first government, when Zvulun Hammer and Yitzhak Levy (National Religious Party) served consecutively as education ministers (Hammer passed away in mid-term).

There is no doubt that the book was written in the spirit of secular liberalism, and was never completely (if at all) to the liking of the political Right and religious circles, even though the book was also designed for the National Religious education stream. The fact that the book emphasized incoherencies in Israel’s definition as a Jewish and Democratic State did not help endear it to the critics. It was only a matter of time before there were demands to rewrite it.

One of the problems with this process has been the way successive education ministers, from Sa’ar, through Shai Piron (Yesh Atid) and down to Naftali Bennett (Bayit Yehudi), have set about the re-write. A significant number of writers, from various ideological persuasions, have been involved in writing different chapters, but without any promise that what they were writing would not be altered, both in letter and spirit, without their being consulted first.

In the current, and apparently final stage of the process, numerous experts have been asked to read the texts and express their opinion. However, the impression one gets is that those who are playing a decisive role in determining the final shape of the book – including constitutional lawyer Dr. Aviad Bakshi from Bar-Ilan University and the Ono Academic College, who was appointed academic adviser for the re-write – know exactly what they want, and thus the attempt to give the process a pluralistic appearance is a deliberate misrepresentation of the reality.

At the moment the public debate is going on – both inside and outside the Knesset – without copies of the new version of the book being available to the discussants.

Most of the debate centers on several quotes made public by the textbook’s linguistic adviser, Yehuda Ya’ari, who argued that “the book in its current form is an attempt to carry out a ‘hostile takeover’ of the civic studies subject, by a ‘religionization’ of a subject that is universal and free.”

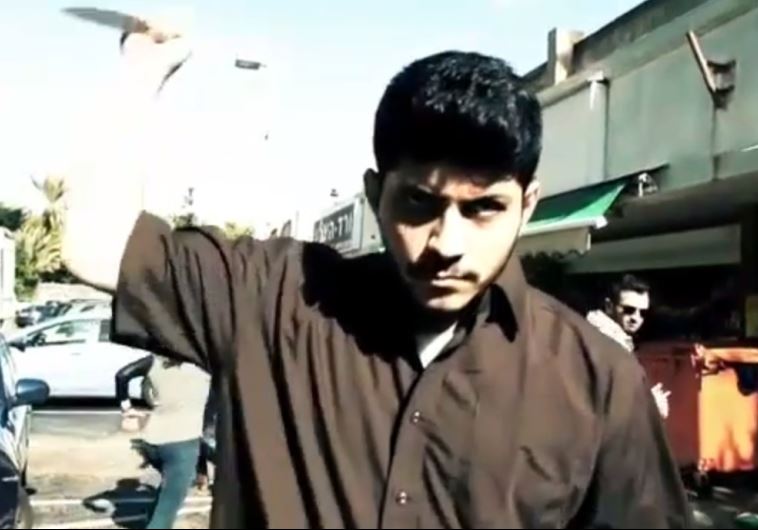

At least two points raised by Ya’ari have already been changed: a statement in the book that most of the stabbings that have occurred during the recent outbreak of violence were perpetrated by Israeli Arabs – which is simply untrue – was deleted (how did it get into the book in the first place?), as was the combination under a single heading of the sinking of the Altalena, the murder of Peace Now activist Emil Grunzweig and the assassination of prime minister Yitzhak Rabin as examples of violence against a political-ideological background.

This coming week the Transparency Committee, chaired by MK Stav Shafir (Labor) is planning to hold a debate on the issue – if it can manage to get a copy of the book. Whether or not a copy will be made available is yet to be seen. It is clear that no serious debate can be held just on the basis of what an ideologically motivated linguistic adviser revealed, and which the Education Ministry claims to be inaccurate.

Of course, it is perfectly legitimate for the ministry to introduce changes in the curriculum – even major changes. Unfortunately the process resembles war and deception more than an attempt to find workable solutions that everyone is able to live with in peace. A roundtable held on the subject of the teaching of civic studies held at the Israel Democracy Institute in the beginning of November, in which the central spokesmen for both sides of the battle participated, showed just how far apart the two sides are.

But does this really have to be a zero-sum-game? Professor Avraham Diskin, a political scientist, who is the author of an alternative, middle-of-the-way (as between Left and Right) civic studies textbook Regime and Politics in Israel – the Foundations of Citizenship, which he published privately in 2011, has actually suggested that under the circumstances perhaps the teaching of civic studies – at least in its current form – ought to be dropped.

I believe this would be tantamount to throwing the baby out together with the bath water. What would be achieved? The national religious youths in the national school system would not get any tuition in non-religious concepts of democracy. Secular youths coming from right-wing backgrounds at home would not be confronted with basic concepts of both formal and substantive democracy? Should there not be an attempt made to convince Israel’s Arab youths that democracy is not just an empty word when it comes to them? Presumably the two sides in the current debate can agree on quite a bit – if they would set their minds to doing so rather than to scoring points against each other as they are currently doing. Why can’t they sit down and delineate the differences, and simply present these differences in concrete terms, without trying to prove that one side is right and the other wrong, or that one side is superior to the other.

While answering questions in the plenum the other day, Education Minister Naftali Bennett spoke out in favor of encouraging classroom debates on the controversial issues. But how can there be serious debate when the controversies are not laid out fairly and squarely, without one side or the other being placed in the defensive? Finally, a word of protest. Anyone who defines secularism, as the new book allegedly does, as “the denial of obligatory religious faith” has no idea what he is talking about. One can practice religious coercion (as is the case in Israel with regard to one’s personal status), but no one can force anyone to believe. Secularism is a matter of the free, democratic choice to reject religion, and it is as legitimate as religious belief.